|

News Feature - November 2004

En Français |

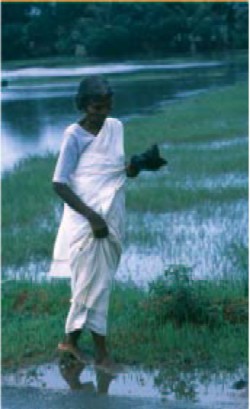

The mosquitos that transmit Japanese encephalitis breed in rice paddies and standing water

|

Japanese encephalitis:an orphan disease comes of age

A lethal disease that threatens 3 billion people throughout Asia and the Pacific is finally getting the attention it deserves, as Dr Julie Jacobson explains.

After years of neglect, efforts to control Japanese encephalitis (JE) have received a major boost with the launch by PATH of a new project to help improve the prevention and control of this ‘orphan’ disease.

Funded by an initial US$27 million, five-year grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, PATH’s Japanese Encephalitis Project (JEP) aims to improve data on the distribution of disease, accelerate the development of diagnostic tests and an improved vaccine, and help countries integrate JE vaccine into immunization programmes in countries in Asia and the Pacific where the disease is found.

According to Dr. Mark Kane, director of the Children’s Vaccine Program at PATH, “over the past few decades, JE has extended its grip on countries across Asia and has become the continent’s leading cause of viral encephalitis. Recent large outbreaks in India and Nepal are raising fears that JE is spreading even more rapidly than we thought.”

Difficult to diagnose – and severely underreported at 30000-50000 cases a year – the mosquito-borne disease mainly affects children between the ages of 1 and 15 years. About 15000 deaths a year are reported. Of the children who develop the disease, about 70% either die or suffer some form of long-term neurological disability, including paralysis, movement disorders, mental retardation and behavioural problems. There is no specific treatment for the disease.

Efforts to control JE are hampered by the lack of a safe, effective and affordable vaccine that can be integrated into routine immunization programmes and by the lack of a low-cost diagnostic test for the disease. The new project aims to tackle both of these problems. In the initial phase, the JEP is focusing mainly on support for the development of diagnostics and efforts to improve surveillance. |

JE has spread steadily in countries in Asia and the Pacific since it was first diagnosed in 1871. Source: Children's Vaccine Program at PATH

|

Improving diagnosis and reporting

At present, there are no commercially available diagnostic tests for JE. As a result, doctors and public health officials in the countries affected are often unable to identify JE, which is difficult to distinguish from other diseases that affect the brain and nervous system. To confirm the presence of the virus, doctors have to take a sample of serum and/or cerebral spinal fluid seven days after the onset of symptoms, and these must be tested for antibodies in a laboratory. One week after the onset of illness, almost all samples will be positive. Countries with successful control programmes have usually combined diagnosis of the clinical encephalitis syndrome with laboratory tests in a subset of “sentinel” hospitals – to estimate what percentage of neurological disease nationally is due to JE and monitor the impact of control programmes.

In an effort to improve the diagnosis and reporting of JE, the project is supporting efforts to develop an ELISA diagnostic test for JE, which should become available this year. The project team is also looking into an innovative information system for JE surveillance in India.

The Surveillance Information Management System (SIMS) will enable health workers in the field to report and access disease incidence data via phone or the Internet – providing a model for information sharing that can potentially be scaled up to subregional and national levels.

Preventable – for some

Many countries have tried to curb JE through efforts to control its vector - the mosquito - and its main host - the pig. However, success to date has been limited and costly. The Culex mosquitos that transmit JE breed in rice paddies and standing water - making them very difficult and expensive to control in Asia. Insecticide- treated bednets have only limited impact as the mosquitos bite in the early twilight when most at-risk populations are not in bed. Experience in several countries has shown that immunization is the only reliable effective control measure. WHO recommends the use of the currently available JE vaccine in all endemic areas where affordable. |

About the virus

JE is caused by an arbovirus in the Flaviviridae family that is similar to West Nile virus. It is spread by mosquitos that lay their eggs in quiet pools such as rice-paddy fields or drainage ditches. The natural transmission cycle of JE is among pigs, wild birds, and mosquitos. Humans and horses are dead-end hosts that do not contribute to the spread of the disease. Pigs are believed to be the source of infection for most human cases. However, birds such as herons and ducks have also been implicated. |

An effective vaccine against JE was developed in 1941 and is used to control the disease in richer countries and to protect travellers, but it has not reached many of the poorest countries in Asia. JE vaccine is routinely used in Japan, Thailand and China, and on a limited scale in Viet Nam, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Following the introduction of vaccination programmes in Japan and the Republic of Korea, the disease effectively disappeared in humans - although the virus remains active in animal populations.

Despite the evident successes of JE vaccination, at-risk countries have, for a variety of reasons, been slow to adopt the existing vaccine. For a start, the current JE vaccine is expensive – at US$9 - US$15 for the three doses needed to fully immunize a child. In addition, the vaccination schedule for JE often begins after a child’s first birthday and requires three doses at irregular intervals over the next 12 months - making it difficult to integrate the vaccine into routine immunization programmes. These problems are compounded by a vaccine production process that is costly and an end product that is difficult to produce in large volumes. The current supply is insufficient to vaccinate all children in the at-risk countries. As a result, there is now growing interest from the international community in a second-generation vaccine to combat JE.

New vaccines needed

To successfully control JE in all affected countries, a new vaccine must be affordable, safe and effective, and fit easily into routine immunization. Several second-generation candidate vaccines that could meet this need are in varying stages of development. China produces three vaccines. Of these, the most interesting is a live, attenuated JE vaccine (SA14-14-2). Available since 1988, it has been administered to over 200 million Chinese children, with good disease control and no reports of serious complications. Studies of the vaccine in use outside China showed the efficacy to be over 95%, with no serious adverse events. However, this vaccine is not yet widely licensed for use internationally and is not pre-qualified by WHO for distribution.

China also produces two other vaccines, available for use only in China. Elsewhere, several manufacturers in the US, Europe and Asia are also working on candidates that would be improvements to the current inactivated vaccine. One promising candidate is a “chimeric vaccine” – so-called because it is made by combining parts of the current yellow fever vaccine with parts of the JE virus.

PATH’s JE project is working closely with WHO, the International Vaccine Institute (IVI) in the Republic of Korea, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNICEF and other partners to catalyze more interest in a reliable, efficacious vaccine against Japanese encephalitis. With this new initiative, for the first time there is a real prospect of controlling this devastating disease.

Dr Julie Jacobson is Director of the Japanese Encephalitis Project at PATH.

Immunization Forum November 2004 -

Contents

|