|

SPECIAL FEATURE - March 2001

En Français

First, do no harm

Lisa Jacobs examines the road to injection safety – from recognition of the problem to action

Look what I’ve found: children playing with discarded syringes |

YOU may already know: unsafe injection practices spread disease. In a tragic twist of irony, health workers who aim to improve people’s health may be unintentionally spreading harm with every prick of an unsterile needle, every time they toss a used disposable syringe in a vat of warm water for eventual re-use, or drop it in a trash can.

The result? From 8 million to 16 million new hepatitis B infections, 2.3 million to 4.7 million new hepatitis C infections and 80,000 to 160,000 new HIV infections every year. These chronic infections are responsible for an estimated 1.3 million early deaths and lead to US$ 535 million in direct medical costs every year.

Injections are prescribed for a wide variety of reasons. While they are essential for delivery of vaccines and many treatments, they are also given for other, questionable reasons. The belief that an injection is the most powerful and quick way to deliver medicine – even if the syringe contains nothing but vitamins – contributes to over-demand for, and over-prescribing of, injections. In fact, the majority of injections given for curative reasons in developing countries are thought to be unnecessary.

Why are unsafe injections tolerated – by health workers, patients, caretakers, government officials? The answers are complex and include economic imperatives and cultural attitudes about waste. But perhaps the most important reason is that the people with decision-making power – including patients and caretakers of children – do not understand the risks, the extent of the problem, or that solutions (Box 1) are well within reach.

According to Dr Yvan Hutin, an epidemiologist and hepatitis B expert who runs the Safe Injection Global Network (SIGN), understanding the problem is the first and most crucial step.

In fact, in many cases, as soon as people see the evidence of what is occurring, they are convinced they must do something about it, says Dr Hutin. "The problem of unsafe injections will not solve itself. But when safety is included in health sector plans and budgets, it will improve."

A problem with clear solutions

In 1995, a study in Burkina Faso found that only one in ten injections in rural health centres was performed with sterile equipment. A new system was then introduced that made essential drugs – including disposable, sterile syringes – readily available at every health centre through a cost recovery scheme. Five years later, the impact on safety was astounding: by 2000 nearly 100% of injections in the centres surveyed were given with a sterile syringe. In this instance, increased supply of syringes led to increased demand – a demand for which people were willing to pay.

"The Burkina Faso experience shows how incredibly amendable this problem is," said Dr Hutin. "Sometimes it is just a matter of making clean needles available."

The supply, or logistics, approach that worked in Burkina Faso will not be the answer for all countries. Demand led to supply in Romania, where a highly publicised outbreak of HIV infections occurred among orphans in the early nineties. Children had been infected through blood transfusions and injections conducted in orphanages.

With the vivid images of medically-induced HIV infection, concern about contracting diseases from syringes built among the general public. People demanded new syringes, in sealed packages, for every injection, and the system responded.

"Every time an intervention has been funded and attempted, regardless as to whether it was behaviour change, provision of supplies or sharps waste management, it showed some impact," says Dr Hutin. "So if we have a sector wide approach that combines all these low-cost interventions, we should be able to eliminate unsafe injection practices."

EPI: a small part of the problem, a big part of the solution

Even though immunization injections account for fewer than 10% of the 12 billion injections given annually, most health systems have considered injection safety the responsiblity of the immunization programme, or EPI. Unfortunately, that responsibility has not been supported with appropriate budgets. And even though it is essential that immunization programmes have safe practices, EPI managers have no control over the use and over-use of injections in the greater health system.

"We can’t solve the problem," says Dr Caroline Akim, EPI Manager in Tanzania. "But we can act as advocates, and push the health system to address it." In fact, advocating for safe injection policies and practices is an opportunity for immunization programmes to have a profound, system-wide impact.

The first priority, according to many, is to adopt a policy on safe injection and disposal. "Having a system-wide policy is necessary to extend responsibility for injection safety to the whole health sector, instead of just in EPI," says Dr Akim. A national policy also gives programmes the authority to seek out and put an end to actions that are unsafe.

However, a policy is only as good as its implementation. Without buy-in by all stakeholders, a safe injection and disposal policy will just be another rule on the books – one that may be considered a nuisance, adding costs to programmes and perhaps even depriving people of much needed income.

"A policy that is not followed is just like having no policy at all," said Dr. B. Wabudeya, Minister of State for Health in Uganda. And the danger is that those in roles of responsibility may think that once a policy is drafted and adopted, the situation has been addressed.

Measuring the problem

If discovery is the first step toward solving the problem, the first step has just been made easier. A simple, focused methodology for tracking injection and disposal practices, and documenting knowledge and understanding among health workers and patients, has just been developed jointly by SIGN, the World Health Organization and BASICS, a programme funded by the US Agency for International Development. Referred to as ’Tool C’ (as in, third of a series of four), this new methodology has been tested in Burkina Faso, Niger, Ethiopia, Mali, Mauritania, Zimbabwe and Egypt(1). The aim is to make it as easy for governments to monitor injection safety as to monitor the percentage of all children immunized, or coverage. "What is the good of increasing coverage if you also increase exposure to hepatitis B and C, or HIV?" asks Hutin.

The methods behind Tool C are simple. In each country, a team of 12 monitors activities in 80 health centres in 10 districts over 2 weeks. Importantly, the data collected are practical, so countries can quickly identify solutions. For example, the team finds out how many health centres have dedicated areas for the preparation of injections, and whether they have at least a week’s supply of disposable/AD equipment in stock. The measures are standardized, so, as more countries undertake the process, common problems can be highlighted and appropriate actions designed.

Dangerous waste

Tool C identified a serious problem in Burkina Faso, one that has caught many communities unprepared. Investigators found needles discarded in open containers in 66 health centres, putting health workers at risk of accidental needle-stick injuries. At most of the centres, used needles and syringes were found in the surrounding environment, putting the larger community at risk – a situation that has been identified in a number of countries.

"In many developing countries, collection and removal of waste is considered to be a municipal responsibility – not that of the hospitals and health system," says Annette Prüss, from the environmental safety division at WHO. "The concept of ’polluter pays’ is a very Western concept."

Not only do children find syringes to be effective squirt toys; in many countries, scavengers also scour refuse for saleable items. Conventional disposable syringes can be rinsed, re-packaged and re-sold as new, when they are not in fact sterile. According to environmental experts, some health workers actually collect used syringes to sell to recyclers, providing income for both. And risk for many.

Now, having learned of their waste disposal problem, health officials in Burkina Faso have developed plans to address it. Their chances for success are high; a recent assessment in Côte d’Ivoire found that facilities which took responsibility for healthcare waste as part of their duty of care successfully eliminated dirty sharps from their environment.

"What is needed above all is the will to take care of the problem," says Dr Hutin.

Technology to the rescue?

Many countries are addressing injection safety by making the switch to AD syringes for immunizations. AD syringes have a mechanism designed to lock the syringe once it is used, so that it cannot be re-used. Countries that have been approved to receive vaccines from GAVI and the Vaccine Fund will also receive the requisite number of AD syringes. GAVI is now weighing a policy to further help countries with the transition from sterilizable and/or disposable syringes to AD syringes for all vaccines, in order to support countries to comply with the policy of WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA to use AD syringes for all immunizations by 2003.

But when it comes to safety, technology is not the entire solution. "If you want to learn how to re-use an ’auto-disable’ syringe, come to Pakistan," says Johnny Thaneoke Kyaw-Myint, Senior Project Officer for Health and Nutrition with UNICEF Pakistan. He was, of course, not serious. "People have learned how to manipulate the syringe so that the safety mechanism doesn’t catch. So it can be re-used, or sold and re-used, again."

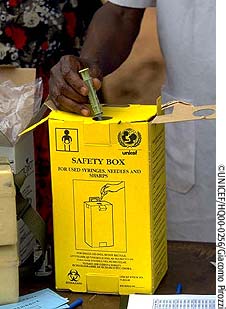

A good start: safety boxes reduce the risks but their final disposal must be safe too |

The lesson? People must be educated, motivated and supported to insist upon a sterile syringe with every injection. Provision of safe injection equipment should be part of a broader strategy that also includes encouraging behaviour change and the management of sharps waste.

At present, 500 million AD syringes are produced annually for use in developing countries. Within two years, as more and more countries follow, that number is expected to rise to 2 billion. The disposal issue becomes more critical each day.

Simple actions can be taken immediately, says Dr Prüss. Supplies of sharps boxes should be available in all health centres – not just in time for immunization campaigns. Small incinerators can be built; local oven-builders can be employed to build incinerators. The costs are affordable; a small incinerator to serve a district can be built for under US$700, according to Dr John Lloyd, an immunization expert with the Bill and Melinda Gates Children’s Vaccine Program at PATH.

Until recently, the problem of unsafe injections seemed insurmountable, says Dr Hutin. "But in fact, when one looks at the experience acquired, we now know that safety is an area that is easy to address – if the health system decides to address it. We know some simple strategies to follow, and results are visible and quick."

Reference

(1) Full series and available summary results at: http://www.who.int/injection_safety/toolbox/resources/en/

|

Country file 1: Pakistan – a country ready for change

SOME would be daunted by the scale of the challenges facing Pakistan’s newly formed injection safety network. But Dr Arshad Altaf, one of the key organisers of the network, does not sound like the daunted type.

"There are no short cuts; we need education and training, and we need injection safety to get the attention and priority that it deserves," says Dr Altaf, a medical doctor and behavioural epidemiologist from the Aga Khan University in Karachi.

The burden of bloodborne infections in Pakistan is heavy. As many as one in ten of the general population is a chronic carrier for hepatitis B virus (HBV). And, in the past few years, hepatitis C virus (HCV) has spread rapidly; in some parts of Pakistan, more than one in 20 people are chronic carriers. Researchers have concluded that unsafe injections are the most likely cause of this growing HCV epidemic. And since HCV is even more likely than HBV to cause chronic liver disease, the burden of long-term illness is rising.

Unnecessary injections

Studies in Hafizabad, southwest of Lahore, and Darsano Channo, near Karachi, both found that exposure to injections was the strongest risk factor for being infected with hepatitis; the more injections, the greater the probability of being infected (1) .

"Painkillers, antibiotics, antimalarials, steroids and multivitamins are all given by injection," says Dr Altaf. All at a price: patients often pay 30 Pakistan rupees (about US $0.50) for an injection when the whole household’s income is often as low as US$1.60 a day. "When the supply of syringes runs out, the clinics just dip the syringe in water and re-use it," says Dr Altaf.

In a study at Aga Khan University Hospital, Dr Naheed Nabi and others (2) found that most patients believed injections were more effective than oral medications, and were willing to pay more for them. But when told that oral medications are equally effective, four-fifths of patients said they would prefer to avoid an injection.

Interestingly, 91 per cent of the patients who received injectable treatments said that their doctors recommended them, disputing the claim that health workers are merely responding to demand. Only 9 per cent of patients had requested injections.

Recycled syringes

A further problem is waste disposal. "There is no proper management or disposal system for waste," says Dr Altaf. His team have tracked the final destinations of syringes from hospitals and clinical laboratories in Karachi. Many are dumped at community waste sites where scavenger boys collect them and sell them to dealers. Some are also sold to scavengers by cleaners at the clinics and labs.

"The used syringes with needles are sold by the kilogram at up to 10 Pakistan rupees [17 US cents]," says Dr Altaf. Needles are removed by the dealers and are re-moulded. The syringe plastic is washed, crushed and made into granules, which are sold on to the plastic ware industry. A minority of syringes are also repackaged and sold for repeat medical use.

The earnings from the hazardous trade of recycling used syringes might seem small to comfortable outsiders sitting in the industrialized countries. But to people on low incomes, they are significant, says Dr Altaf. "With the financial incentive and the culture of re-use being so ingrained in the country, we expect that recycling will continue," he says.

Educate the scavengers

Pakistan must develop a proper system (3) for clinical waste disposal, Dr Altaf believes. This, together with the eventual use of autodisable (AD) syringes in the country’s immunization clinics, may reduce the risks of bloodborne infections. But until doctors and patients gain a greater understanding of the risks of infection, and the number of unnecessary therapeutic injections falls, large numbers of conventional disposable syringes will continue to enter community waste dumps. Dr Altaf believes that it may be pragmatic to educate those involved in the recycling trade about the risks of infection and create a reliable system for the safe removal and incineration of needles before the syringes are put in the trash. If the recycling of syringes for remoulded plastic cannot realistically be stopped yet, at least the risks to everyone can be reduced.

In the short year since Pakistan formed its national network for the Safe Injection Global Network, no time has been wasted. Today, the network’s activities are beginning to bear fruit: the country has recognized the scale of its problem and – crucially – most stakeholders in the health system are now keen to do something about it.

References

(1) Presentation at SIGN Pakistan symposium, February 2000, by Dr Stephen Luby, CDC, Atlanta USA.

(2) Presentation at SIGN Pakistan symposium, February 2000, by Dr Naheed Nabi, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.

(3) For an update on current WHO policies and activities on healthcare waste disposal, see http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs253/en/

Phyllida Brown |

|

Country file 2: Egypt: ‘We need to decrease the demand for injections’

EGYPT knows better than most countries the human cost of re-using needles. An astonishingly high proportion of the population – about one in eight people – is infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and hepatitis B is also widespread (1) . Much of this disease burden is attributed to unsafe injections. The problem is not new, but today there is a new and powerful commitment to overcoming it.

"Injection safety and infection control have become high priorities of the Ministry of Health and Population," says Dr Maha Talaat, a public health specialist and executive manager for a new programme in the ministry. The programme’s goal is to prevent the transmission of bloodborne pathogens in the health service. Dr Talaat is also a member of a new national coalition of health workers that is striving to increase awareness of injection safety issues.

Part of Egypt’s problem can be traced back to a mass treatment for schistosomiasis before the 1980s. The treatment required multiple injections and is believed to have spread HCV widely (2) . But new cases of HCV infection have continued to appear today, even though the schistosomiasis treatment has long been replaced. Researchers believe that re-used needles are still to blame. Today, studies suggest HCV continues to be spread by unsafe injections and other healthcare practices.

Most of the injections are unnecessary. "People prefer injections to oral medications because they think that injections will cure them faster," says Dr Talaat. "We need to decrease the demand for injections."

The government has planned its response carefully. This year, the new programme is gathering essential baseline data so that it can measure the impact of interventions that will start next year, including training for healthworkers, education and mass media campaigns for the public, and action to ensure that supplies of sterile injection equipment are available at all times.

The top priority, Dr Talaat believes, is to educate those who deliver the injections. The first step is to identify who they are. The team has already discovered, from a study in one governorate, that more than 40% of injections in this setting are given not by trained healthworkers but by lay people including relatives, friends and "health barbers", whose services are cheaper than those of doctors. These findings, and further studies to find out healthworkers’ practices across the country, will be crucial in the design and targeting of training material.

Another key priority is safer disposal systems for clinical waste, says Dr Talaat. "The Ministry of Environmental Affairs, together with the Ministry of Health and Population, are working to try to solve this problem," says Dr Talaat. Because there is no proper system for the transport and incineration of clinical waste, all syringes – whether or not they are in safety boxes – are a hazard once they leave the healthcare facility. Some find their way to municipal rubbish dumps where children play with them. If the final disposal system is not properly managed, says Dr Talaat, no type of equipment, including safety boxes or autodisable (AD) syringes, can be regarded as safe.

No one doubts the scale of the challenge facing Egypt. But now it is recognized. And, with a new government programme and an active coalition of healthworkers determined to achieve change, the battle has begun.

References

(1) WHO press release: http://www.who.int/inf-pr-2000/en/pr2000-14.html

(2) Frank et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. The Lancet, 2000, 355: 887-891.

Phyllida Brown |

Immunization Focus March 2001 - Contents

|

|