|

Immunization Focus

August 2000

Return to Aug 2000 contents page

SPECIAL FEATURE

The invisible culprit

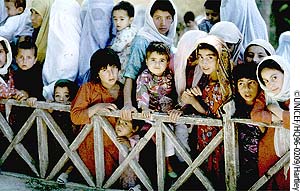

An avoidable disease continues to kill more than a thousand children every day. Phyllida Brown finds out why, and asks what is being done to overcome the problem

IT has been virtually eliminated from the industrialized countries. Safe, effective vaccines that protect infants from it have been licensed for about a decade. Yet in many developing countries, the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) goes almost unchecked. Worldwide it is estimated to kill 400 000 to 500 000 young children each year. Most die of pneumonia, and a smaller number from meningitis. So far, very few developing countries use Hib vaccines in routine immunization programmes (see Map ). Why? First, because the vaccines are relatively expensive. Even though prices have fallen sharply, the cost of a three-dose schedule is still at least US$6, compared with just cents for traditional vaccines such as diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP). Second, and equally important, many governments are simply not convinced that the disease is a problem in their country. Despite being one of two leading causes of pneumonia, Hib can be difficult to diagnose, so its role often goes unrecognized.

Now, however, years after international efforts began in earnest to increase children’s access to Hib vaccines in developing countries ( 1 ), some key gains have been made. First, researchers now have dramatic and solid evidence of the impact of these vaccines on the incidence of pneumonia and meningitis in some low-income countries ( 2 ). This evidence has helped to clarify the size of the Hib burden. Second, cost-effectiveness estimates suggest that, provided Hib vaccines are delivered within existing immunization programmes, they can deliver excellent returns. And third, convinced that the introduction of Hib vaccine is a sound investment for countries’ health systems, the GAVI Board has decided that low-income countries should receive at least initial funding from the Vaccine Fund to do so.

Source: WHO

Hib vaccines are safe and effective. The World Health Organization has published a position paper on Hib which concludes that, "in view of the demonstrated safety and efficacy of the Hib conjugate vaccines, Hib vaccine should be included&. in routine infant immunization programmes" ( 2 ). WHO recognizes that individual nations must take account of their own capacity and priorities in deciding whether to adopt the vaccine, but, overall, supports its use.

Yet despite WHO’s position, and even with the prospect of new funding in the short term, many countries’ health officials consider Hib to be a relatively low priority among under-used vaccines, preferring instead to introduce immunization against hepatitis B, a virus whose prevalence is relatively well known. In some cases, governments fear that the addition of Hib vaccine to their immunization programmes will strain already-overstretched systems.

Still a low priority

For example, in Mozambique, the national immunization programme is not considering introducing this vaccine at the moment. "The programme does not have the capacity for the introduction of a new antigen," says Rose Macauley, technical adviser to the programme at the Ministry of Health. Even in countries that are keen in principle to introduce Hib, there is a need for data to justify the decision. "We would like to introduce Hib vaccine, but we have no concrete data or statistics on the burden," says Eva Kabwongera, project officer for UNICEF in Kampala, Uganda. She contrasts this with the situation for hepatitis B. "For hepatitis B we have the statistics, we have identified it as a burden, so it is appropriate to introduce the vaccine." In Sub-Saharan Africa only Kenya, Malawi and Rwanda have so far requested support for Hib in their proposals to GAVI and the Vaccine Fund, although a group of countries in West Africa including Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Togo is also planning to work with partners to introduce Hib.

|

Box 1: Hib: the basics

- Among all strains of Haemophilus influenzae, type b accounts for about 90 per cent of the invasive disease. Hib disease kills an estimated 400 000-500 000 children each year

- An estimated 3 million cases of severe disease are attributed to Hib each year. One in five children who develop meningitis suffer permanent brain damage

- In industrialized countries before immunization was widespread, meningitis was the most frequent manifestation of Hib disease, but worldwide there are probably about five cases of severe Hib pneumonia for every case of Hib meningitis

- Hib resistance to antibiotics is growing

- Since the introduction of conjugate Hib vaccines from 1990 onwards in industrialized countries, the incidence of invasive Hib disease in these countries has fallen by more than 90 per cent

- Outside the industrialized countries, Hib vaccines have been shown to protect against meningitis and pneumonia in Chile, Uruguay and The Gambia

|

For Jay Wenger, coordinator of the Accelerated Vaccine Introduction Priority Project at WHO, the invisibility of Hib is a key reason for the lack of demand in many countries. "People are not going to introduce a vaccine for a disease they cannot diagnose," he says. Among the diseases that doctors see regularly, pneumonia is among the most common – but its causes are multiple and the Hib cases look no different from the others. The bacterium is difficult to isolate without invasive procedures and special laboratory materials that may not be available in some developing countries. "If you never isolate the bacterium, then the clinicians are unlikely to think about the disease," says Wenger.

And even when samples are obtained, infection may be masked in children who have been treated indiscriminately with inappropriate antibiotics. Although a few large city hospitals in Sub-Saharan Africa do perform laboratory diagnoses of Hib disease, data on the burden of disease due to the microbe have not been widely disseminated.

Measuring the burden

Joel Ward, director of the UCLA Center for Vaccine Research in Torrance, California, believes that there is also a problem of perception. In some countries Hib is wrongly perceived to be a problem only of the industrialised world. "I have been told that Hib is a Western disease," he told delegates at the Third Annual Conference on Vaccine Research in Washington, DC, earlier this year. Yet antibodies to Hib are found in all populations, as are the diseases it causes.

Since the mid 1990s, however, the evidence that Hib is a major cause of pneumonia worldwide has strengthened dramatically. In The Gambia, West Africa, between 1993 and 1995, researchers assessed the impact of a Hib conjugate vaccine on the incidence of pneumonia overall in a double-blind trial involving more than 40 000 infants. They found that in the Hib-vaccinated group, the incidence of severe pneumonia, diagnosed on chest X-ray, was reduced by 21 per cent ( 3 ). By implication, the researchers concluded, one in five episodes of severe childhood pneumonia in the Gambia is Hib-related. This is at least twice as high as earlier estimates, which had attributed at most 10 per cent of pneumonia episodes to Hib. Adding weight to these findings, researchers in Chile have performed similar studies and found very similar results ( 4 ). With the aim of increasing the spread of data in Asia, a similar Hib vaccine trial, with a measurement of the impact on pneumonia overall, is under way in Lombok, Indonesia, coordinated by the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health and the France-based nongovernmental organization, Association pour l’Aide à la Médecine Préventive (AMP). For English or French briefings, see www.aamp.org

|

Box 2: Is there an evenly distributed burden of Hib disease worldwide?

Based on the available estimates, the incidence of invasive Hib disease varies between regions.

- In the US before widespread immunization, there were an estimated 40 to 60 cases of Hib meningitis and an estimated 67-130 cases of all Hib disease per 100 000 children under 5 years of age annually.

- Sub-Saharan Africa appears to have similar or greater rates for Hib meningitis.

- Asia, by contrast, may have a lower incidence of the disease with estimates of less than 5 cases of Hib meningitis per 100 000; yet Hib has been found to be the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in most hospital-based studies, including in Asia.

- Further studies in China, Korea and Vietnam are under way to quantify the burden in Asia further.

- Latin American studies at the end of the 1980s, before the introduction of vaccines, suggest that, for the region overall, there were 15 to 25 cases of Hib meningitis per 100 000 children, and 21 to 43 cases of all Hib disease. However, more population-based studies are needed to confirm these estimates.

|

Because of the growing data on the importance of Hib, the GAVI Board has concluded that there is justification for introducing the vaccine in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas and the Middle East. Countries in Asia may also be justified in introducing Hib if epidemiological data confirm the need. Indeed, one of GAVI’s targets is to introduce Hib vaccine to 50% of high-burden, low-income countries by 2005 ( 5 ).

Rapid assessment tool

But many countries prefer to have their own data on the size of the Hib burden before they go ahead and introduce the vaccine. "The problem is that, at the moment, countries still have to take the WHO’s word for it," says Wenger. "So it is still not a definite buy-in." Thus there is also a need for a tool to enable governments to rapidly assess the burden of Hib in their own population. To this end, WHO, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other partners have been developing such an assessment tool. Chris Nelson at WHO describes how it works.

First, officials scour the records of the main hospital in a district to identify all logged clinical cases of meningitis over a set period, usually 12 months. They also check laboratory records for microbiological records of Hib meningitis and cross-check lab data with clinical records. The number of Hib meningitis cases, set against the whole population in the district under age 5, gives an estimate of the incidence of this condition. Measuring Hib pneumonia is more difficult, but the trials in The Gambia, Chile and elsewhere suggested that there are about five pneumonia cases to each meningitis case in a year. First, officials scour the records of the main hospital in a district to identify all logged clinical cases of meningitis over a set period, usually 12 months. They also check laboratory records for microbiological records of Hib meningitis and cross-check lab data with clinical records. The number of Hib meningitis cases, set against the whole population in the district under age 5, gives an estimate of the incidence of this condition. Measuring Hib pneumonia is more difficult, but the trials in The Gambia, Chile and elsewhere suggested that there are about five pneumonia cases to each meningitis case in a year.

The rapid assessment tool assumes a similar ratio and uses the meningitis incidence figure to estimate the pneumonia figure. Field tests of the tool have begun: six countries have already either tested it or have planned to test it over the coming weeks, says Nelson. "We are moving very quickly," he says. There will be a meeting in October and a draft by the end of November, says Nelson.

With better data on disease burden, says Tore Godal, Executive Secretary of GAVI, many countries will see the benefit of introducing the vaccine.

But affordability continues to be a concern to many governments, given that commitments to immunize children must be sustained well beyond the five years of support from the Vaccine Fund. Nonetheless, different strands of evidence suggest that the cost should not be seen as an insurmountable barrier. First, an increasing number of studies indicate that Hib vaccines are cost-effective. In January 2000, researchers commissioned by the former Children’s Vaccine Initiative published estimates of the cost-effectiveness of Hib in Sub-Saharan Africa which indicated that vaccine could be delivered for US$21-22 for each year of healthy life gained ( 6 ). That would make the vaccine an excellent "buy", given that, according to analyses performed for the World Bank, any health intervention that costs less than $25 per year of healthy life gained would be regarded as a highly cost-effective investment ( 7 ). Earlier studies by the same researchers had also indicated that the vaccine could be cost-effective in low-income Asian countries.

Cost savings

There are also some individual national studies, including some that actually predict cost savings – rather than just cost-effectiveness – from Hib immunization. For example, in an analysis published in 1995, researchers in South Africa measured the costs of the disease against the benefits of the vaccine there. They calculated that the estimated economic costs of Hib disease in the 1992 Cape Town cohort ranged from Rand 10.7 million to R11.8 million. The costs of introducing the vaccine would have been less, amounting to R8.3 million. They concluded that the vaccine�s benefits would have exceeded its costs in Cape Town alone by up to R3.5 million (US$500 000) – a substantial return ( 8 ). Since 1999, South Africa has introduced Hib vaccine into its national immunization programme.

|

Box 3: Hib vaccines

The new generation of "conjugate" Hib vaccines contain two components - the Hib polysaccharide capsule and, attached to it, a "carrier" protein antigen such as tetanus toxoid that stimulates a strong, T-cell related, immune response. These vaccines are effective in infants and reduce the number of Hib bacteria carried by healthy people in their nasopharynx, reducing the spread of Hib infection not only in vaccinated but also unvaccinated people. There are several licensed Hib conjugate vaccines, including combinations with DTP and DTP and hepatitis B. |

Impressive as the data on investment returns may be, some governments nonetheless are still likely to find $6 or more per immunized child unaffordable for the longer term. This situation may change, however, as the cost of the vaccine continues to fall or as resources are freed up for immunization from other sources.

As for the strain on overstretched immunization programmes, Wenger argues that the difficulties may have been overstated. WHO and the other partners in GAVI strongly advocate the use of combination vaccines where possible, and some combinations of Hib and DTP are available (see reference 5 ).

As countries grapple with competing demands on their highly restricted resources, Hib vaccine may not appear to be a top priority today. Yet, when in future the vaccine is introduced, and the crushing burdens of childhood pneumonia and meningitis begin to lift, health workers and parents may look back with astonishment at the reasons given for delaying now.

Key references

1. The CVI seeks speedy Third World adoption of Hib vaccine. CVI Forum 12, August 1996, pp 2-9.

2. WHO Position Paper on Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines. Undated. www.who.int/vaccines-diseases/diseases/hibpospaper.shtml

3. Randomised trial of Haemophilus influenzae type-b tetanus protein conjugate for prevention of pneumonia and meningitis in Gambian infants. Mulholland, K. et al., Lancet 349:1997;1191-1197. ( Medline ).

4. Defining the burden of pneumonia in children preventable by vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type b . Levine O.S. et al. Paediatric Infectious Disease J. 1999. 18:1060-4.

5. Guidelines on Country Proposals for Support to Immunization Services and New and Under-used Vaccines. GAVI and The Vaccine Fund. Available at www.VaccineAlliance.org/download/guidelines.doc or from the GAVI secretariat.

6. Policy analysis of the use of hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type b, Streptococcus pneumoniae -conjugate and rotavirus vaccines in national immunization schedules. Miller M. and McCann L. Health Economics, January 2000.

7. Jamison, D. et al. (Eds). Disease control priorities in developing countries. Oxford University Press. 1993. New York.

8. The costs and benefits of a vaccination programme for Haemophilus influenzae type B disease. Hussey G.D., et al. South African Medical Journal 1995 Jan:85(1):20-5.

9. Cost-benefit analysis for the use of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in Santiago, Chile. Levine O.S., et al. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1993. 137:1221-8.

10. Wenger J.D. et al. Introduction of Hib conjugate vaccines in the non-industrialized world: experience in four "newly adopting" countries. Vaccine 2000:18:736-742.

Vaccine impact graphs are adapted from The Jordan Report 1998. NIAID, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Return to August 2000 contents page

|

|