|

||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

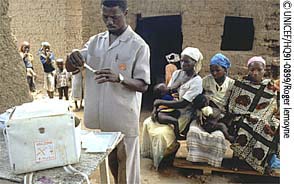

Return to May 2000 contents page May 2000 BRIEFING The right combination Vaccines that immunize against several diseases at once have obvious advantages. But how many are available for use in developing countries? Lisa Jacobs finds out THE more diseases an immunization programme can prevent, the better: few health officials would argue with that. But every addition of a separate new antigen into a vaccination schedule requires another shot, another needle and syringe, and extra disposal costs. And, just as important, the extra responsibility on over-burdened health systems may also increase the risks of unsafe injections.

Because of its widespread use, ease of administration, and three-dose schedule given in infancy, it has become the foundation of routine immunization coverage. DTP has also become the foundation upon which many of the existing combinations have been built, including those relevant to GAVI:

Part of the reason why the list is so short is that many high-income countries are not interested in buying vaccines that contain whole-cell pertussis, preferring instead the acellular pertussis (DTaP), despite its higher price. This reduces the incentive for companies to develop combinations containing the whole-cell preparation.

"My calculation is that when you take all costs into account – logistics, labour, compliance issues and the risk of unsafe injections – combination vaccines are definitely not more expensive than individual antigens," he says. Furthermore, as more of these vaccines are purchased for the developing-world market, prices could drop. There are precedents: when it was first introduced, Hepatitis B cost US$25 per dose; now it is well under US$1. And as recently as 1998, Latin American countries were purchasing Hib vaccine directly from manufacturers for as much US$8.50 per dose. Now the Pan American Health Organization is able to offer the vaccine to its member states for US$3.00 per dose, according to estimates for the year 2000. As demand for these new and under-used vaccines increases, more companies may enter the market. The process may take some time, however. Combining existing antigens is not a simple development, but poses complex technical and clinical challenges, since the combined product has to demonstrate equivalent safety and immunogenicity. New combination vaccines must undergo extensive clinical trials to ascertain whether the different components, including the individual antigens, stabilizers and preservatives, have had negative effects on efficacy. The regulatory process alone can take three to five years, and adds to vaccine’s cost. "There is no way to avoid combination vaccines in the future and we should be prepared to have more and more of them," says Jacques-François Martin, CEO of Parteurop. "But making things easier also makes things more complicated. A company that holds the market position today could lose everything tomorrow if it does not include a particular antigen in its combinations. Market forces will no longer be able to dictate future vaccine needs. We will have to agree on certain orientations today in order to provide the world with vaccines they can use in the future." *Two versions of DTP are available: the ’whole-cell’ pertussis and ’acellular’ pertussis (DTaP), approved for use because of minor side effects that can occur with whole-cell pertussis. Lisa Jacobs is Communications Officer for the GAVI Secretariat

Return to May 2000 contents page

|

|||||||||||

| Contact GAVI | Guestbook | Text version | Credits and Copyright

|

|||||||||||