| ||||

| | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

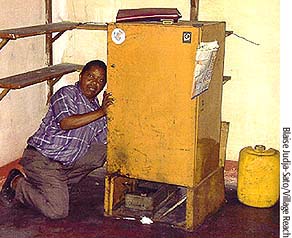

October 2001 Return to October 2001 contents page BRIEFING How the fridge loses its cool Failing refrigerators are preventing effective immunization in a large number of health centres. Phyllida Brown finds out why, and hears about new approaches to keeping the cold chain cold THERE may be nothing glamorous about a refrigerator. But as anyone involved in immunization knows, it is one crucial tool in enabling all children to receive the vaccines they need. Disturbingly, however, the performance of the refrigerator in thousands of health centres in low-income countries is so poor that regular effective immunization becomes impossible, some children are left unprotected, and expensive vaccines may be wasted.

"We have a widespread problem with the management and the maintenance of the equipment," says Modibo Dicko, of WHO’s African regional office in Harare. Hard data are scanty, but individual reports from countries in Africa indicate that up to one in four health centres cannot offer immunization regularly because of refrigerator failure. These figures are probably representative of the region, says John Lloyd, formerly head of the cold-chain section in the Expanded Programme on Immunization at WHO, and now at the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH). Souleymane Kone, a logistics specialist for WHO in Côte d’Ivoire, presented an assessment of overall vaccine management in 13 African countries to the Technical Network for Logistics in Health (TechNet) meeting in Delhi last August. The assessment found consistent problems with the maintenance and supply of spare parts for fridges1. African countries are not the only ones with a problem. Refrigerator failures are also common in South Asia, where surveys and repair programmes have been undertaken by IT Power India, a private consultancy specialising in environmental and renewable energy solutions, based in Pondicherry. In one of the most severe examples, in Bihar, about half of the cold chain equipment was not working when it was surveyed in 1998 prior to a repair programme. A survey this year in Nepal suggests there are widespread problems there too2. Many refrigerator breakdowns are due to interruptions in the supply of spare parts. Many of the parts are actually consumables such as wicks, fuel and glasses for kerosene-run units which account for many of the refrigerators used to store vaccines. A key reason for supply problems is weakness in the management of the system, so that spare parts are not ordered efficiently, stock is controlled poorly and then not delivered where it is needed. "Things tend to fall apart," says Mr Lloyd, "and often there will be no automatic system for reordering." Where spares are ordered in a haphazard fashion, they may end up in the wrong place or being misused for other purposes. "You need a guaranteed flow of spare parts," says Mr Lloyd. In principle this should be easy to achieve, since the lifetime of the consumables is predictable.

With a limited budget and a limited supply of government technicians, most health districts cannot get repairs done when they need to. As a result, says Dr Dicko, in the African countries where the problem has been studied, up to 70% of health districts’ maintenance is done by private-sector technicians, some of whom may not have the specific parts or skills needed. "It is easier to call the local handyman and give him the job," says Dr Dicko. "But if they don’t have the right spare part, then the equipment remains out of action." More recently, private-sector electricians have been invited to join courses, and have accounted for about half the trainees. Some governments and non-governmental organizations are exploring the use of the private sector, not just for technicians, but for the maintenance of the whole cold chain. Their reasoning is that a for-profit company may have greater incentives than a public-sector body to ensure its equipment is maintained and its staff retained. "When you walk into a shop to buy cola, the fridge is working," says Mr Lloyd. In a privatised system, the company buys the cold-chain equipment from the government and then takes rent in return for a properly maintained system, paying its technicians and taking responsibility for ordering parts, stock control and distribution. Côte d’Ivoire, for example, has just entered a five-year contract in which the entire cold chain is outsourced from the Ministry of Health to a private company. If the experiment works well, other countries may follow, says Dr Dicko, although he warns that some governments are resistant to the idea. Another approach, now being advocated in Nepal by IT Power’s Terry Hart, is to encourage decentralization of cold-chain maintenance. When other aspects of the health system are decentralized, maintenance may be best done by small community organizations. Management of the cold chain within the country is key, but another problem is ensuring the procurement and delivery of spares into the country in the first place. The majority of countries have no manufacturing capacity for the spares themselves. UNICEF, long responsible for the procurement of vaccines for the Expanded Programme on Immunization, has also taken responsibility for procuring cold-chain spares. Mikko Lainejoki, of UNICEF Supply Division in Copenhagen, says: "Whenever we supply a considerable number of cold chain units we always emphasize the need to include spare parts as a part of the initial purchase. The aim is to set up a system for regular routine replenishment of spare parts." However, for this system to work properly, the government needs to ask UNICEF for enough spares and the spares need to arrive on time. Neither is always the case. Supplies stuck in port Recently, some governments have started procuring spare parts for cold chain equipment using their own budgetary sources, rather than having them supplied by UNICEF. Usually, they continue to buy through UNICEF’s own procurement mechanism, as in the case of India. UNICEF itself is exempt from paying import taxes, but if a government is paying for its own spares, the Ministry of Health may have to pay import tax on them. Funds for these taxes – required because countries are attempting to broaden their tax base – are supposed to be covered by a line item in each country’s health budget, or may in some countries eventually be reimbursed by the finance ministry. But, whether through lack of funds, communication breakdown, or poor management, tax payments sometimes fail to materialise, leaving supplies in port and causing further delays in the delivery of equipment. Mary Ann Carnell is technical director of a family health project in Madagascar for John Snow Incorporated, an international health consultancy, and the US Agency for International Development. The project works with the Madagascan Ministry of Health. She says that spare parts for vaccine refrigerators have sat in port there for up to two years in the recent past because of tax problems. The problems are now being resolved, she says, but there are still severely frustrating delays with the delivery and distribution of spares and the Ministry of Health is considering several options, including tenders for domestic suppliers, and tenders by the central medical store, a private non-profit organization, to ensure parts arrive promptly in future. Funding is another problem. The cost of spares is high relative to the original refrigerators, says Lloyd. Manufacturers tend to make a very small profit on the original goods, making their profit instead on the sale of spares. With budgets stretched, governments find it difficult to foot the bill. However, few donors have been willing to invest in either spares or cold-chain maintenance, regarding these as recurrent rather than capital costs and therefore governments’ responsibility. A soluble problem "The entire management of the issue should be addressed," says Dr Dicko. "From forecasting the need for equipment, to installing it, to making sure that the fuel is available, to making sure that spare parts are always available, to making sure that temperature is monitored regularly. All these things are crucial." And, he stresses, while maintenance can be outsourced to the private sector, other important tasks, such as monitoring performance, must still be taken care of by the public sector. Ultimately, the refrigerator problem seems more soluble than many facing immunization programmes. But it has remained neglected. With the advent of the new "dollars-per-dose" generation of vaccines, donors will be keener than ever to see waste reduced, and governments will want to ensure good vaccine management. "The Alliance partners should be doing much more," says Dr Dicko. "They should start lobbying the donors to focus on this issue."

Source: DANIDA 1988

References 1. Kone, S. Presentation to TechNet 2001, New Delhi. www.who.int/vaccines-access/Vaccines/Vaccine_Cold_Chain/technet/TC21_kone.pdf 2. Terry Hart, CEO, IT Power India, personal communication. IT Power India is a subsidiary of IT Power Ltd., UK. www.itpower.co.uk

Phyllida Brown

Return to October 2001 contents page

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contact GAVI | Guestbook | Text version | Credits and Copyright

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||